A group of about twenty veterans gathered near a bridge along the west branch of South Carolina’s Stono River in the early morning light of September 9, 1739. These were no provincial militiamen, but African slaves. With their appointed leader Jemmy directing, the Africans broke into a nearby storehouse kept by Robert Bathurst and a Mr. Gibbs. The rebels immediately seized the building’s store of firearms and ammunition, decapitated the two storekeepers, and laid their heads on the front stoop as they moved on. The band of rebels turned south, next plundering and burning the Godfrey plantation where they killed two more white planters. As the march continued, more unsuspecting colonists would meet a similar fate. One colonist recalling the incident reported that “they killed all the white people they found” along the Pons Pons Road. By noon, at least twenty white colonists lay dead in their wake. This rising would become the largest and bloodiest slave rebellion in the history of mainland British North America, yet its origins and explanations make it more than just a provincial American story.

The rebels gained followers as they marched, and soon their numbers swelled to nearly one hundred armed men. They constructed banners for their march and began to beat on drums to set the pace in military fashion. As news of the slave rising spread, Lieutenant Governor William Bull “raised the country,” mustered the militia, and rushed to intercept the Africans near the Edisto River. Meanwhile, the band of rebels halted in a field near the river during the early afternoon. There, they performed traditional war dances, sang songs in Portuguese, English, and African dialects, and continued to beat the drums in the hopes of drawing more escaped slaves to their ranks.

The rebels gained followers as they marched, and soon their numbers swelled to nearly one hundred armed men. They constructed banners for their march and began to beat on drums to set the pace in military fashion. As news of the slave rising spread, Lieutenant Governor William Bull “raised the country,” mustered the militia, and rushed to intercept the Africans near the Edisto River. Meanwhile, the band of rebels halted in a field near the river during the early afternoon. There, they performed traditional war dances, sang songs in Portuguese, English, and African dialects, and continued to beat the drums in the hopes of drawing more escaped slaves to their ranks.

In typical slave insurrections the mere sight of armed troops could cause escaping slaves to surrender, and Bull must have counted on this when he arrived with a mixed command of mounted planters and infantry militia at four in the afternoon. These slaves, however, in uncharacteristic fashion “behaved boldly” and fired two organized volleys before the white planters could respond. Caught off guard, Bull’s men nevertheless returned fire, killing or wounding at least fourteen rebels. At this point, many of the latecomer slaves either surrendered or turned and fled. An organized unit of the rebellion’s leadership, however, retreated across the river in good order. With nightfall approaching, Bull and his militia could not safely pursue their retreat.

The leaders of the initial insurrection were reportedly “Angolans” and suspected to have connections with Spanish Florida. They spoke Portuguese, which many South Carolinians understood to be “a dialect of Spanish, such as Scots is to English” and demonstrated certain adherences to the Catholic faith. One South Carolina planter around this time complained that “many Thousands of the Negroes profess the Roman Catholic Religion,” having learned its tenants in Africa before being brought to the New World. It is unclear what happened to the surviving rebels after a week of intermittent skirmishing, but it is quite possible that they made it to Saint Augustine, their initial objective, or joined Creek Indians in the borderland between Georgia and Florida, where many runaway slaves found asylum during this period.

The rebellion baffled colonial officials in South Carolina and sent fear through the wider American colonies. A slave revolt of this magnitude was unprecedented on the North American mainland and the strange, “bold” behavior of these slaves, their effective use of firearms, and their apparent military organization troubled planters and officials, who needed explanations for such anomalies. When war broke out between Britain and Spain just a month later, planters in South Carolina were quick to blame Spanish priests and colonial agents based at Saint Augustine for inciting the insurrections. The slaves’ intentions had fled toward Spanish Florida and many of the rebels were Catholic; it seemed like a tidy way of explaining away the organized resistance of the slaves.

Historians followed suit with this explanation and for centuries, the standard interpretation cited Spanish instigation as the source of the rebellion. However, in recent decades, as scholars have expanded their gaze to take in not just European perspectives, but broader Atlantic explanations for historical events, the exceptional events of the Stono Rebellion begin to take on a distinctly African background.

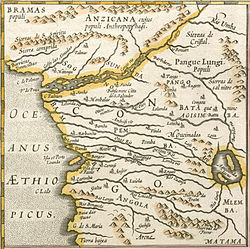

Significant components of the rebelling slaves in the Stono River revolt were misidentified as “Angolans” because of their ability to speak Portuguese and their adherence to Catholicism. In the early eighteenth century, however, most actual Angolan slaves were shipped directly from the Portuguese colony across the southern Atlantic to Brazil. When South Carolinians employed the term “Angolan,” they were more likely referring to the  coast of West Central Africa, which British ship captains called the “Angolan Coast.” The port of Kabinda, near the mouth of Zaire River, served as the main point of embarkation for the slave trade in the region, and many of the Africans brought to South Carolina in the opening decades of the eighteenth century arrived in Charles Town from there.

coast of West Central Africa, which British ship captains called the “Angolan Coast.” The port of Kabinda, near the mouth of Zaire River, served as the main point of embarkation for the slave trade in the region, and many of the Africans brought to South Carolina in the opening decades of the eighteenth century arrived in Charles Town from there.

While Kabinda was the port of origin for South Carolina’s slave majority, the slaves themselves came from the vast African interior. Distinguishing actual identities and backgrounds of African slaves is often impossible. Given that the leaders of the Stono Rebellion spoke Portuguese and practiced Catholicism, it seems likely that they came from the Kingdom of Kongo, the only region of West Central Africa with a long history of exposure to both the Catholic Church and Portuguese traders.

Kongo, in the last decades of the seventeenth and early years of the eighteenth centuries was a war torn kingdom. Since 1665, several factions had fought for control of the Kongolese crown, each vying for support from the Portuguese that traded along the coast and the Italian Capuchin monks that brought Catholicism to the interior. In spite of  perennial civil war, Kongo was one of the most cosmopolitan kingdoms in West Central Africa at the time. At the behest of shifting monarchs, the Capuchins had built schools and churches throughout the hinterland. Kongolese enjoyed a high literacy rate, and were accustomed to dealing with Europeans, having steady contact with the Portuguese from the sixteenth century on. By the early decades of the eighteenth century, Kongo was also experiencing an era of military innovation. Competing factions for the throne began enlisting massive armies and utilizing firearms procured from Dutch and Portuguese traders along the coast.

perennial civil war, Kongo was one of the most cosmopolitan kingdoms in West Central Africa at the time. At the behest of shifting monarchs, the Capuchins had built schools and churches throughout the hinterland. Kongolese enjoyed a high literacy rate, and were accustomed to dealing with Europeans, having steady contact with the Portuguese from the sixteenth century on. By the early decades of the eighteenth century, Kongo was also experiencing an era of military innovation. Competing factions for the throne began enlisting massive armies and utilizing firearms procured from Dutch and Portuguese traders along the coast.

Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita

At the turn of the eighteenth century, war raged as João II of Lemba challenged Pedro IV of Kibangu for control over the Kongolese crown. In 1704, the tumult in Kongo reached new levels as Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, young woman claiming to be the reincarnated Saint Anthony, began to gather Afro-Catholic followers in the Mbanza region. She called for an end to the civil war while amassing an army of her own. Dona Beatriz’s ranks grew to over 40,000, and in 1705, the “Antonians” marched on the ruined capital of São Salvador and occupied it. From her new headquarters, Dona Beatriz negotiated an alliance with João, hoping to consolidate a front against the Portuguese-backed Pedro. The Antonians had bargained on the wrong ally, however, and with the campaign of 1706, João was killed in battle and his forces collapsed against Pedro’s advancing armies.

In the same campaign, Pedro intercepted Dona Beatriz. Pedro, with Portuguese and Capuchin support, tried Dona Beatriz for heresy and burned her at the stake in July 1706. Over the next three years, Pedro’s forces waged a war of elimination against the Antonians. The final blow came in 1709 when Pedro took São Salvador and sold the remaining followers of Antonianism into slavery. Scholars now estimate that perhaps as many as 20,000 Antonians became caught up in the trans-Atlantic slave trade over this tumultuous period. Civil wars continued to rage across the Kongolese provinces for another three decades and with each defeat or victory, thousands more captured combatants entered the trans-oceanic world of slavery.

Pedro IV

By taking in this African element of the story, which for years was either unknown or ignored, a fuller picture of the Stono Rebellion emerges. Thousands of slaves in South Carolina had West Central African origins. Many of these Africans were enslaved during the Kongo civil wars, explaining their Catholicism and Portuguese language. It seems clear that at least the leadership along the Stono River had military experience, familiar with firearms and volley tactics. While colonists may not have understood this Kongolese background, their actions in the aftermath of rebellion are telling. The South Carolina legislature passed the 1740 Negro Bill, which banned slave assembly, and planters petitioned slave importers to avoid any more slaves from the Angolan coast, as “these were perceived more dangerous, and liable to rebel.” After the rebellion, South Carolina importers began to look to the Upper Guinea coast instead, where they hoped to find less dangerous slaves. The varying African origins of slaves influenced how they acclimated to New World slavery, and shaped the broader history of early America. Along the Stono River in 1739, the distinct background of a group of Kongolese veterans enabled them to harness their military experiences from Africa to resist bondage across the Atlantic, in South Carolina.

Enjoyed our article? Check out another about slaves whose skill in iron works gave them more leverage in the New World.

Comments or questions? Leave one below!

————————————————————————–

Sources:

“An Account of Negroe Insurrection” in Candler, Allen, and William Norton, eds., Colonial Records of the State of Georgia (1904-16; rpt. edn., New York, 1970).

Berlin, Ira. The Making of African America : The Four Great Migrations. New York: Viking, 2010.

Heywood, Linda M., and Thornton, John K. Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Thornton, John K. “African Dimensions of the Stono Rebellion.” American Historical Review 96, no. 4 (1991): 1101-1113.

Thornton, John K. The Kongolese Saint Anthony Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-1706. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Wood, Peter. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.