On June 17, 1957, Sam Battistone and Newell Bohnett saw the first fruits of their entrepreneurial vision ripen along Cabrillo Boulevard in Santa Barbara, California. Hoping to tap into blue-collar workers and middle-class vacationers, they opened up a joint-venture pancake and coffee house featuring moderate prices. Coffee sold for a dime a cup and a stack of pancakes cost only 40 cents. Grasping for a name both could agree upon, the partners combined their names, Sam and “Bo,” to create “Sambo’s.” The name worked in another way, too. Their hopes of building a pancake franchise and the clever combination of the owners’ names fit with a popular children’s story about a boy named Sambo who ate 169 pancakes. The two decided it would make a perfect marketing theme with “excellent promotional potential,” and soon, colorful billboards were popping up across Santa Barbara to tempt would-be patrons.

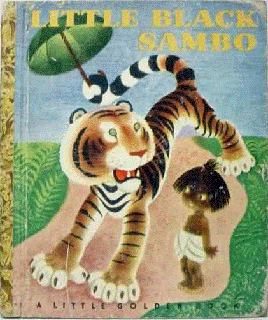

Battistone and Bohnett drew upon the children’s book Little Black Sambo for their marketing platform. Originally written in 1899 by Helen Bannerman, the wife of a British colonial agent in Madras, Little Black Sambo tells the story of a South Indian boy who contends with four tigers in the jungle one day. Unwittingly outsmarting the hungry predators with his flashy new cloths, Sambo eventually tricks the tigers into chasing one another to exhaustion, when they all melt into a giant puddle of ghee, or Indian-style clarified butter. Sambo scoops up the tigers-turned-butter, takes them home, and has his mother make a feast of pancakes out of their remains.

While British children came to love the tale, critics from the beginning noted its racialized components. Bannerman named Sambo’s parents Mama “Mumbo” and Papa “Jumbo,” a clear derogatory reference to the languages of India. By the end of the story, readers find Sambo stripped down to the stereotypical loincloth of Indian characters like Kipling’s Mowgli and Gunga Din. Bannerman called him “black” Sambo not as the cultural identifier familiar to the United States, but as a  racialized descriptor in use throughout the British Empire. Dark skinned South Indians were often called “blacks” by British colonizers, just as South African Zulus, Sudanese Berbers, or Australian Aborigines were in other parts of the empire. Overall, the storyline casts Sambo as an infantilized, somewhat helpless, comedic figure that lucks out in the end—a role resonating with British imperial thought of the day that saw the brown races of the world as childlike peoples to be cared for and ruled over.

racialized descriptor in use throughout the British Empire. Dark skinned South Indians were often called “blacks” by British colonizers, just as South African Zulus, Sudanese Berbers, or Australian Aborigines were in other parts of the empire. Overall, the storyline casts Sambo as an infantilized, somewhat helpless, comedic figure that lucks out in the end—a role resonating with British imperial thought of the day that saw the brown races of the world as childlike peoples to be cared for and ruled over.

While the caricaturing of Indian people in the British Empire at the height of its power may not be much of a surprise, the story took a twist as it left England’s shores and came to America in 1900. Here, the story entered a society that already knew the term “sambo” in a different context, and that background would transform the face of Bannerman’s protagonist.

In the United States, both whites and African Americans had used “Sambo” as a racial slur denoting a “loyal and contented” black servant or slave—someone who was either too lazy, unintelligent, or childish to think for themselves or work towards their independence. British slavers in the Caribbean had first adopted the term from the Spanish word zambo in the eighteenth century during the Asiento trade. In New Spain, zambos were one of many racial categories in the Casta system, which had been created to chart and condemn racial mixing among colonial peoples. Zambos were the offspring of American Indians and Africans, but as the term adapted in the plantation system of the antebellum American South, “sambo” became a distinctly African American designator.

So when audiences, conditioned to the racial dichotomy of Jim Crow America, read Little Black Sambo and saw a helpless dark skinned boy playing in the jungle, they invariably envisioned the character as African American. US-based printing houses, hoping to cash in on the story’s popularity, followed suit. While readers remained implicitly aware that the setting was supposed to be India, their point of reference remained the segregated racial landscape of America. Soon, illustrators were drawing Sambo not as a south-Indian boy, but in the image of a racialized pickaninny character. The Indian ghee simply became butter, and Mama Mumbo took on the costume of a mammy figure from the antebellum South. Mainstream white culture embraced the book and its new imagery, and Little Black Sambo became a children’s bestseller in the U.S. Famous illustrator John R. Neill  signed on to sketch the images for the official 1908 reprinting in the States, and within a decade of the story’s appearance in America, hundreds of counterfeit versions, all uniquely illustrated, were also being printed.

signed on to sketch the images for the official 1908 reprinting in the States, and within a decade of the story’s appearance in America, hundreds of counterfeit versions, all uniquely illustrated, were also being printed.

With each reprinting and copycat version, the drawings became more egregious in their exaggerated racial caricatures. According to Alice Schreyer, director of Special Collections at the University of Chicago, eventually “it became incendiary.” Many African Americans, all too familiar with the harsh side of such stereotypes, condemned the books’ renderings to little avail. Langston Hughes famously criticized the work in 1932 for its representation of black youths, saying the story and characters might be “amusing undoubtedly to the white child, but like an unkind word” to African Americans “who had known too many hurts to enjoy the additional pain of being  laughed at.” Despite the protests of Hughes and others, the story remained a pop culture hit as a children’s book. In 1935, Cinecolor even released an eight-minute Comicolor cartoon, where Sambo acts out the stereotypical role of a comedic African American, falling into trouble despite his mother’s warning that, “that old tiger sure do like dark meat,” in the dialect of the slave South.

laughed at.” Despite the protests of Hughes and others, the story remained a pop culture hit as a children’s book. In 1935, Cinecolor even released an eight-minute Comicolor cartoon, where Sambo acts out the stereotypical role of a comedic African American, falling into trouble despite his mother’s warning that, “that old tiger sure do like dark meat,” in the dialect of the slave South.

Such popular images were what Battinstone and Bohnett hoped to capitalize on with their dining franchise several decades later. Soon after its opening, they commissioned a series of murals that would depict the story of Little Black Sambo on their restaurant walls. Boosted by its storybook theme and affordable breakfasts, the Sambo’s chain quickly became a smashing success, expanding locations across southern California. By 1963, the business partners were tracking $300,000 in sales annually, and at the height of the franchise, Sambo’s boasted 1,117 locations in forty-seven states.

That growth would come to a resounding halt, however, as the business expanded into the Midwest, Northeast, and South in the late 1970s. Unlike the West, which had remained a minor arena in the era of Civil Rights, these eastern regions had been the battleground of racial desegregation during the Sixties, and progressive passions still ran high a decade later. As new restaurants went up across Michigan, Ohio, and Georgia, protesters fought the openings and towns filed zoning injunctions against a franchise that seemed to be serving racial slurs along with its syrupy pancakes. In the 1970s, while Americans were becoming more aware of the racial inequalities between blacks and whites, Asian and Indian figures nevertheless remained an easy target. Sambo’s tried to counter the animosity over their “black” caricatures by changing their logo back to a more “south Asian” character, by lightening Sambo’s skin to a distinct tan and adding a turban.  Sambo’s executives hoped that by opting for a comedic portrayal of an Indian, they might draw less flak from African American veterans of the Civil Rights Movement. In a desperate attempt at survival, the marketing directors ironically reverted to the storyline’s original racialized caricatures of South Asians to distance their restaurants from the uniquely charged racial politics of black and white America.

Sambo’s executives hoped that by opting for a comedic portrayal of an Indian, they might draw less flak from African American veterans of the Civil Rights Movement. In a desperate attempt at survival, the marketing directors ironically reverted to the storyline’s original racialized caricatures of South Asians to distance their restaurants from the uniquely charged racial politics of black and white America.

But the name itself remained a central complaint of the chain’s antagonists. In Rhode Island, the Human Rights Commission declared the use of the term Sambo “had the effect of notifying black persons that they were unwelcome at Sambo’s restaurant because of their race.” In Massachusetts, a local Urban League blocked the corporation because the name itself “carried racial overtones.” By 1980, the NAACP had filed a series of lawsuits against the chain over its name. The company’s executives argued that the restaurant’s appellation was simply a play on the first names of its founders, Sam and Bo, but eventually the pressure was too much. In the South, the chain became known as “No Place Like Sam’s” while in the Northeast restaurants reopened as “The Jolly Tiger.” The shift proved too little too late, and by 1982, the franchise filed for bankruptcy.

Today, only the Santa Barbara location survives. Chad Stevens, the grandson of Sam Battistone, still runs it under the original name and dreams of expanding the franchise again one day. During an interview in 2014, Stevens told journalist Andrew Romano that he still does “get the occasional complaint,” but he has “a hard time” seeing how the restaurant remains offensive. He reflected, “maybe being white or Anglo-Saxon, maybe I’m not seeing  something.” It is interesting to note that Stevens himself ascribes to a wider white Anglo-Saxon identity, despite the fact that his grandfather founded the company as the son of Italian immigrants.

something.” It is interesting to note that Stevens himself ascribes to a wider white Anglo-Saxon identity, despite the fact that his grandfather founded the company as the son of Italian immigrants.

While the original murals so offensive to African Americans are long gone, paintings of the updated Indian caricature—Sambo in a Sikh turban—hang in their place, bringing the stereotypical figure full circle, back to the racialized world of British India. Whether in its Indian or African American context, the story of Sambo still paints the brown minority figure as a racialized and exoticized caricature for white American consumers. Moreover, the persistence of the Indian caricature, coupled with the public outcry over the African American version, shows that racial politics in America remains dominated by the black and white dichotomy. But the story of Sambo and his many caricatures shows that race relations transcend a simple American context. Across the Anglophone World, British heirs in places like South Africa, Australia, the U.K., and Canada have contended with the complicated issues of polyglot race over the postcolonial decades. As the United States continues to struggle with the changing landscape of race going forward, part of the solution might involve accounting for this wider context.

Sources:

Atkinson, David C. The Burden of White Supremacy – Containing Asian Migration in the British Empire and the United States. The University of North Carolina Press, 09.

Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence : Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. America and the Long 19th Century. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press, 2011.

Golus, Carrie, “The University of Chicago Magazine: Chicago Journal.” Accessed March 27, 2017. http://magazine.uchicago.edu/1010/chicago_journal/sambos-subtext.shtml.

Jeyathurai, Dashini. “The Complicated Racial Politics of Little Black Sambo.” Text. South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA), April 4, 2012. https://www.saada.org/tides/article/20120404-703.

Joseph. Boskin. Sambo the Rise & Demise of an American Jester. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

LaMotte, Greg, “CNN – Sambo’s Revival Running into Hot Water – January 28, 1998.” Accessed March 27, 2017. http://edition.cnn.com/US/9801/28/sambo.revival/.

Lester, Neal A. “Can a ‘Last Comic Standing’ Finally Rescue Little Black Sambo from the Jungle?” Valley Voices: A Literary Review 12, no. 2 (2012): 108–139.

Mielke, Tammy. “Transforming a Stereotype: Little Black Sambo’s American Illustrators.” Cambridge Scholars, 2011.

Pilgrim, David. “The Picaninny Caricature.” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. October 2000. Ferris State University.

Romano, Andrew. “Pancakes and Pickaninnies: The Saga of ‘Sambo’s,’ The ‘Racist’ Restaurant Chain America Once Loved.” The Daily Beast, June 30, 2014. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/06/30/pancakes-and-pickaninnies-the-saga-of-sambo-s-the-racist-restaurant-chain-america-once-loved.html.

Sircar, Sanjay. “Little Black Sambo: Perplexities and Patterns.” Journal of Children’s Literature Studies 3, no. 1 (2006): 40–71.

Yuill, Phyllis J. Little Black Sambo: A Closer Look : A History of Helen Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo and Its Popularity/Controversy in the United States. New York: Racism and Sexism Resource Center for Educators, 1976.

Nice blog thanks for poosting

LikeLike