Senator Daniel Webster squirmed in the pew of the South Haven Presbyterian Church one Sunday morning in 1827. He and a friend, Philip Hone, had come to the small Long Island village for a weekend of fishing after their local friend, Samuel Carmen, had reported sightings of large sea-run trout in the East Connecticut (now Carmans) River and the pond of Fireplace Mills. For several years, Webster had obsessively pursued the large fish of the Long Island rivers without success. In 1823, he had come across on a ferry from New York City to see a monster of a trout caught by Carmen, weighing upwards of thirteen pounds. Since then, he had come annually in pursuit of a similarly magnificent fish.

As the service concluded, Webster and Hone rushed back to Carman’s millpond, where a slave called Lige had been posted to watch for trout while they were away. Lige pointed out a deep pool where he had watched a big fish swimming the hour before. Daniel Webster prepared his fifteen-foot hickory rod, nicknamed “Old Killall,” and cast for the pool. On the second cast, as a crowd of parishioners looked on from the churchyard, an incredibly large fish surfaced and took Webster’s bait. Webster reared back on his rod and battle ensued. The old fish jumped, rolled, and dived through the pond as Webster struggled to inch it towards shore. After twenty minutes of fighting, the leviathan finally yielded to the net. Carman weighed the incredible fish on his gristmill scales at 14 ½ pounds before packing it for shipping in ice and sawdust. That night, back in New York City, Webster and a group of friends dined on the fish at Delmonico’s, where there was reportedly “plenty of trout flesh for all.”

So goes the legend.

Many have questioned whether Webster was actually the man that landed the fish. Martin Van Buren, Philip Hone, and Samuel Carman himself also fished the river regularly, and several reports of 14-pound bruisers filtered back through the New York papers from 1820 through 1827. But this history is less about the man, Webster, and more about the trout that he pursued.

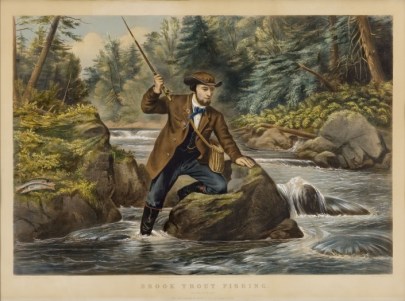

While many iterations of the event have made the specifics fuzzy, the fact remains that large trout once haunted the waters of the eastern United States, and during the 1820s, Samuel Carman, Daniel Webster, and many other Americans captured enormous fish in the ten, twelve, and fourteen pound range. It might surprise readers that the trout captured in the Webster tale was a brook trout. Today, brook trout still swim in the streams of Long Island, but rarely exceed 8 inches in length. Anglers nowadays use diminutive flies and lightweight tackle to land such quarry, which are measured in ounces, not pounds. While brook trout retain a small following of nostalgic fishermen, American anglers have largely moved on to pursue more exciting trophies, like lunker largemouth bass and quick-striking steelhead, which both grow to enormous size and offer sporting battles. These species now loom large as America’s great fish, but there was a time, not that long ago, when brook trout dominated the dreams of American anglers.

Brook trout are the only char native to eastern North America, and for centuries, they cruised waters from Georgia north to Labrador and west to Minnesota, occupying minuscule beaver ponds and mountain streams as well as the largest east coast rivers and interior Great Lakes. Many Native Americans valued them for food, while some, like the Iroquois, revered them as a protected creature of the spiritual realm. Brook trout naturally thrive “in clear, well-oxygenated, cold, rapidly moving water,” and most rivers in the east provided this ideal habitat in the pre-Colombian and early American period. A sea-run variety, called “salters” and “salmon-trout” by early colonists, was particularly prodigious in the tidewater areas of New England, New York, and New Jersey, where they exhibited the anadromous qualities of their salmonid relatives, living their life in the near shore ocean before returning to the rivers to spawn. In places like the Long Island Sound, Cape Cod Bay, Narragansett, and the Chesapeake, salter brook trout benefited from the shallow, nutrient rich brackish waters of the coast and the protected spawning beds of the inshore streams, growing to great size. Daniel Webster’s legendary opponent was likely such a salter, spending most of its life in the salt waters off Long Island.

Even inland, large brook trout impressed early settlers, who described them as “cunning and noble quarry” and their flesh as “exceptionally pleasing.” They were the darling of both sporting anglers and hungry fishermen. An early promotional tract boasted about the brook trout “he has gone on being the same sensible, shrewd, wary and delightful fish, adapting himself to all sorts of mountain streams, lakes, ponds and rivers, and always giving the largest returns to the angler in the way of health and happiness.” During the first half of the nineteenth century, and earlier, the brook trout truly was America’s great sport fish.

But as more European colonists began to make eastern North America their home, the land began to change, and with it, the waters. First, the new settlers’ clear cutting and plowing tactics increased erosion rates throughout much of the east. By the time Daniel Webster and Samuel Carman sparred with the brookies of Long Island, trout habitat was already declining. Soil, running off the newly cleared fields of the young republic entered the streams and rivers as silt. This silt covered over the rocky beds needed for spawning and suffocated the aquatic insects that young char relied on for food. With the agricultural expansion of the early nineteenth century came mills, which required dams to operate. While trout in inland streams struggled to find proper breeding beds, those sea-run trout moving upstream along the coast found their spawning routes blocked off by impassable gristmill dams. Farther north and west, in places like Maine and Ontario, lumbering operations further endangered brook trout habitat, promulgating more erosion and opening up shaded streams to the warming influence of direct sunlight.

Spawning brook trout on rocky beds

Later waves of industrialization, pollution, overfishing, and invasive species all took their toll as well, until by 1880 a Minnesota conservation official lamented that “the brook trout is an object of wanton destruction.” Numbers began to drop significantly throughout the brookies’ range, and in many rivers where large trout had thrived, populations became totally extirpated. Journalists in Pennsylvania worried that “fishermen, who for years have matched their skill, cunning, artifice, and prowess against the genuine brook trout” were realizing “the sad truth that like the deer, bear, quail, woodcock, and grouse, brook trout are slowly but surely passing away.” By the turn of the twentieth century, things looked bleak. One melodramatic observer romanticized in 1916, “It is goodbye to the brook trout now. With him it was either cool pools, solitude, and freedom, or total extermination.” The legendary species that had transfixed early settlers and battled with United States Senators had lost its place in both the hearts and rivers of America.

But nature is resilient, and the brook trout persisted, albeit in a stunted, stilted form. Between 1800 and 1900, siltation and other factors compromised approximately 91% of the historical brook trout range according to ecological archeologists. Most eastern rivers now flow warmer and muddier than before, but in the shallower waters upstream, the trout can still survive. Original brook trout habitat still exists, writ small, in the higher elevations of the Appalachian Mountains and some northern tracks of Maine’s wilderness. As fisheries expert Nathan Gillespie stated in a 2011 interview, “brook trout are now relegated to headwater streams,” almost exclusively. While the shallow confines of these waters limit the size of fish, brook trout have adapted to compensate for the cramped “skinny water.” Scientific studies conducted in Georgia, Minnesota, and Maryland all confirm that over the past one hundred years or so, brookies have begun to mature quicker, and at smaller sizes. This allows much smaller fish to reach reproductive age sooner than their ancestors did. In smaller upland waters, thriving populations of smaller fish persist because of this. Even in compromised waters, such as the streams of Long Island, where less than ideal habitat stunts growth and longevity of fish, heritage strains of brook trout continue to survive through earlier breeding cycles.

A typical brookie in eastern waters today

While this is good news in the sense that the brook trout has skirted extinction, it nonetheless means an altered existence for the once dominant game fish. Brook trout are now seldom found over 15 inches, even in the most pristine waters of the eastern United States. In light of a mature 6-inch brookie on the end of your line, old stories such as the Daniel Webster tale begin to sound more myth than fact. It seems hardly believable that a fourteen pound brook trout could have ever existed, anywhere. Some restorative conservationists and wistful anglers are attempting to bring back salter populations in Massachusetts, and in Lake Superior, Canadian and U.S. authorities have begun collaboratively stocking 250,000 brook trout annually in an effort to restore the large specimens that once cruised the Great Lakes. It remains to be seen whether such efforts will pay off in significant ways moving forward. For now, the fate of the eastern brook trout remains a bittersweet tale of endangerment, adaptation and survival. If nothing else, it serves as a reminder that even the species that avoid complete extermination in the wake of human progress are often permanently altered by it.

Rare photo of historically large brook trout

Sources:

“Eastern Brook Trout: Status and Threats” on Oconee River Chapter of Trout Unlimited website: https://orctu.wordpress.com/test/brook-trout/

“Coaster Brook Trout” Fisheries Program- Midwest Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 9 May 2016. Accessible via the web at http://www.fws.gov/midwest/fisheries/coaster-brook-trout.html

Bradford, Charles. The Determined Angler and the Brook Trout: An Anthological Volume of Trout Fishing, Trout Histories, Trout Lore, Trout Resorts, and Trout Tackle, New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons Knickerbocker Press, 1916.

Gorman, James. “Wild Brook Trout Still Thriving on Long Island,” New York Times 5 May, 2002.

Klahowya, Fly Fishing In Wonderland. Chicago: OP Barnes, 1910.

Newman, Lee, and Robert Dubois, Status of Brook Trout in Lake Superior. Ashland, WI: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996.

Poole, Robert. “Native Trout Are Returning to America’s Rivers,” Smithsonian Magazine August, 2007.

Sadler, Thomas. “Bringing Back New England’s Salter Brook Trout” Orvis News, September 2011.

Straw, Matt. “Looking for Bigger Brook Trout” In Fisherman Magazine, 21 Sept, 2011. Accessible via the web at: http://www.in-fisherman.com/straws-blog/7377/

Stranko, Scott, et al. “Brook Trout Declines with Land Cover and Temperature Changes in Maryland,” North American Journal of Fisheries Management 28:1223–1232, 2008.

Winchell, N.A. The Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota. 8th Annual Report for the year 1879. Ashland, WI: 1880.

Often times we tend to think of humans as some sort of outsiders but they are part of the system. Ecosystems change–only humans try to preserve fish in any form. We may not always get it right but I’m proud of the people who make the effort. Life on earth is never static anyway. I’d rather be smaller than dead. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well written!! There are a few places in Washington State and Montana that have Brookies that will get to the three and four pound class but nothing like you are writing about.

LikeLike