Flannel clad, ball cap donned, you can picture him now—the iconic American trucker. He might have a bit of scruff, he might wear aviator sunglasses. He most likely has a caffeine addiction; he could have a hard drug addiction. These are the stereotypes that came to define those in the trucking industry of the 1970s as Americans faced new struggles and looked for glimpses of old heroes in response. For a brief but influential moment in time, truckers embodied this older American form of heroism before falling from pop-culture iconography a mere ten years later.

The image of the trucker as a hero began in late 1973 in response to events far away and seemingly unrelated. In October of that year, on Yom Kippur, an Arab coalition led by Syria and Egypt launched a joint surprise attack on Israel. The war saw Israel, largely supplied by the United States, victorious against the Arab nations in less than a month. Beaten and embittered against the U.S. for having aided Israel, Arab member states of OPEC led by Saudi Arabia declared an oil embargo against the U.S. This, in turn, caused an oil shortage in the United States.

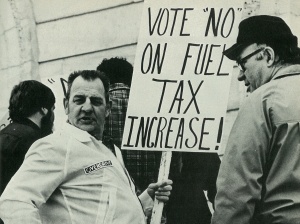

Responding to the crisis, the U.S. federal government began to ration oil and gas and imposed a nationwide 55 mph speed limit on all highways and interstates to promote fuel conservancy. The crisis and subsequent rationing caused gas prices to skyrocket, and coupled with the crackdown on highway speed limits, independent truckers whose profits depended on rapid, gas-powered  delivery struggled to make ends meet. Independent truckers led by Mike Pankhurst, a labor organizer and editor of the trucking magazine Overdrive, went on strike to protest the mounting pressure on small time drivers. While those on strike blockaded freight depots and threatened scabs who continued driving, one of the most effective tactics proved to be the strikers’ use of their rigs to slow traffic, congest beltways and bypasses, and block off roads. Despite their efforts, the strike failed to elevate speed limits to previous levels, and in following years, truckers would have to find other ways to cope with these challenges.

delivery struggled to make ends meet. Independent truckers led by Mike Pankhurst, a labor organizer and editor of the trucking magazine Overdrive, went on strike to protest the mounting pressure on small time drivers. While those on strike blockaded freight depots and threatened scabs who continued driving, one of the most effective tactics proved to be the strikers’ use of their rigs to slow traffic, congest beltways and bypasses, and block off roads. Despite their efforts, the strike failed to elevate speed limits to previous levels, and in following years, truckers would have to find other ways to cope with these challenges.

In the aftermath of the 1973 strike however, truckers came to appreciate their powerful role on the highways of America, realizing their bulky trucks were often the best asset for asserting truckers’ wills. If a truck, or group of trucks, blocked or slowed traffic patterns to demonstrate a protest there was little authorities could do speed them up or move them. Likewise, if a group of powerful semis sped in tandem down a highway, there was little that could be done to stop the rogue drivers. Following the 1973 strike, truckers began to form ad hoc convoys as they traveled across the country in order to stymie law enforcement and usurp the new 55 mph speed limit.

A new technology that made this type of organic cooperation possible beyond the reach of the law was the Citizen’s Band (CB) radio. Truckers illegally adopted coded “handles” (pseudonyms) to identify themselves and communicate back and forth. They developed veiled lingo to mask their conversations from law enforcement. The “front door” (lead truck in a convoy) for instance, would scout the highway ahead for “bears” (state highway patrol, so called because of their hats, evocative of Smokey the Bear) and relay sightings to his fellow convoy members to alert them to speed traps and other potential dangers of the road. Even if caught by surprise by a lurking “bear,” convoy logic reasoned that the state trooper could only stop one truck while the rest of the convoy “put the hammer down” (accelerated) and escaped the scene.

This renegade culture soon caught the eye of the American public. Equally frustrated with governmental and economic developments in the 1970s, Americans saw truckers as the rogue heroes they longed for. Replete with slang names reminiscent of the old west, a healthy disregard  for authority, and a rugged individualism sparked by life on the road, these CB talking truckers loomed large in the American mind. In 1976, C.W. McCall’s song “Convoy,” a fictional account of a truck convoy that runs toll booths from California to New Jersey became the number one hit on both the pop and country charts.

for authority, and a rugged individualism sparked by life on the road, these CB talking truckers loomed large in the American mind. In 1976, C.W. McCall’s song “Convoy,” a fictional account of a truck convoy that runs toll booths from California to New Jersey became the number one hit on both the pop and country charts.

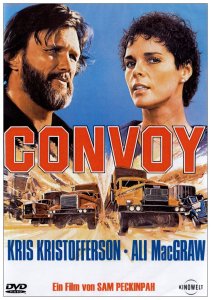

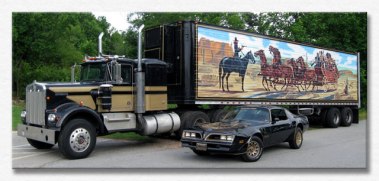

The public became obsessed with truck culture—consumer estimates from the time approximate that before the rise of truckers in the public eye, there were 800,000 CB licenses on the books, but just one year after McCall’s song hit the charts “11 million were in use, many by everyday citizens” trying to tap into the trucker culture. A movie by the same name as McCall’s song, and based on the hit, came out in 1978, starring Kris Kristofferson. The epitome of road culture on the silver screen came with Smokey and the Bandit, a Burt Reynolds film that featured cat and mouse chases between police and the protagonists in convoys of big rigs and muscle cars alike. This movie explicitly embraced the connection that the public saw, or wished to see, between the highway journeyman of the 1970s and the cowboys and bandits of the bygone west.

The famous image on the side of the Smokey and the Bandit truck plays on Wild West imagery: An outlaw dressed in black holds up a stage coach.

As quickly as the truckers rose to national prominence, however, their figure became marred by violence and unease. In 1979, another bout of rising oil prices, this time predicated on the Iranian revolution, threatened truckers’ livelihoods once again. With the rise of their bandit image in the public eye, it seems that many truckers took this outlaw identity to heart during the 1979 crisis. This time, truckers broke out in violence as a response to rising gas prices. In the summer of that year, nearly 100,000 independent truckers went on strike, but their union counterparts kept to the roads. Angered by the lack of solidarity, striking truckers used their CB radios to issue death threats to those who kept driving and threw rocks off overpasses to damage passing rigs. The violence escalated to the point where “gunmen hiding in roadside brush and riding in pickup trucks shot up at least 31 trucks in 18 states.” Truckers embracing their desperado image turned the freighting industry into a wild west shootout over the course of several months.

Such violence did not rest easy with the public. Where authority-flaunting truckers were inspiring and endearing, this darker, more violent image of the trucker was troubling. Several state governors were forced to declare a state of emergency and one even encouraged citizens to carry fire arms to protect against “marauding” groups of truckers. Jimmy Carter echoed public opinion in condemning the violence when he wrote that “none of the problems faced by the independent [truckers] can justify the lawlessness that has occurred.” Main stream entertainment reflected this more sinister shift in road culture, expressing itself in the Mad Max dystopian movie series that incorporated themes of the rising violence among truckers in the late seventies and early eighties, coupled with apocalyptic fears of gas shortages and resource competition.

Violence persisted off and on for several years, and in 1983 when teamster George Capps was shot dead while operating his rig just outside Newton Grove, N.C., pot shots and arson had become regular occurrences in truckers’ strikes. It seemed natural that eventually homicide would enter the scene, almost exactly a decade after truckers had first become a national icon. The renegade star of the trucker, it would seem, had burned out. A more settled American public, recovering from the the cultural, political, and economic strife of the Vietnam era by the 1980s, no longer looked to truckers as some form of blue collar hero. More broadly, western imagery and the allure of the bandit had fallen out of vogue. As violence and criminal activity plagued the trucking industry, it too, fell by the wayside of public admiration.

Like this article? Let us know what you thought in the comments below! We’re always happy to answer feedback.

References:

Lively, Amy. “Truck Driver Strikes of 1979” Trucking History, accessed on CB39.org

Packer, Jeremy. “Mobile Communications and Governing the Mobile: CBs and Truckers.” The Communication Review 5, no. 1 (2002): 39-57.

Pisarski, Alan, and E. Terra. “American and European Transportation Responses to the 1973–74 Oil Embargo.” Transportation 4, no. 3 (1975): 291-312.

“Nation/World: Violence Spreads in Strike by Truckers; 1 killed, 13 hurt Truckers.” Chicago Tribune, Feb 02, 1983.

“Snipers Fire at Truckers Who Don’t Join Full Strike.” Chicago Tribune, Jun 11, 1979.

“Trucks Start Rolling Again Despite Strife.” Chicago Tribune, Feb 09, 1974.

“Truck Strike, Violence Spread.” Chicago Tribune, Jun 22, 1979.

Pingback: ᐅ Die 5 besten Handheld-CB-Radios Testvergleiche 2018 | Beste Vergleiche | Aircon

Pingback: Die 5 besten Handheld-CB-Radios | kelpoo.de

Pingback: Die 5 besten Handheld-CB-Radios - bloggertestlabor.de

Pingback: Die 5 besten Handheld-CB-Radios – sb-testing.de